PLANE CRASHES, IN SLOW MOTION

18th November marks the start of World Antimicrobial Awareness Week.

Health workers, scientists and global institutions like the World Health Organisation will be working hard to increase awareness of global antimicrobial resistance (AMR), and urging policy makers to take swift and firm action to prevent the ongoing emergence and spread of drug-resistant infections.

The misery that coronavirus has inflicted on so many people over the past year has highlighted the cataclysmic impact of health emergencies, that even our advanced technologies and sophisticated minds cannot easily overcome. Not just health impacts, but financial, social and psychological impacts, too. And those impacts will continue, long after the virus has gone.

Which gives me hope that, having seen healthcare and disease control move to the top of the political agenda, governments worldwide may be more receptive to calls for action on other health emergencies, like AMR, and be prepared to proactively address them, rather than focusing on the next short-term vote-winner or burying their heads in the sand.

Because we do need action. Now.

As I have mentioned in previous blogs, the coronavirus pandemic is unfortunately accelerating the rise of antimicrobial resistance. The huge volumes of antibiotics and other drugs being prescribed to treat primary and secondary infections in COVID-19 patients are giving bacteria and viruses the opportunity to develop resistance, spread further and leach into our waste water systems, rivers and oceans.

“Many predicted a global pandemic prior to Covid-19, but the world was still ill-prepared.

We must not be caught out the same way by drug resistant infections, a slow-moving pandemic whose impact we are already seeing today.

We can prevent it from developing into an irreparable crisis but the time to act is now. ”

What’s more, the disruption to health services caused by the pandemic, and delays in the diagnosis and treatment of other infectious diseases are allowing them to spread, too.

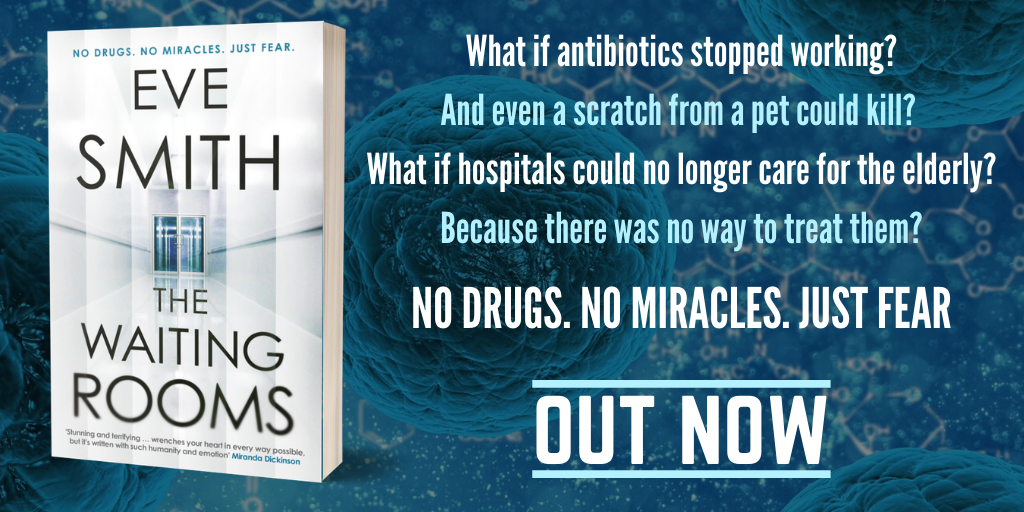

One of those is an age-old foe, and also the trigger for the antibiotic-resistant pandemic in my novel, The Waiting Rooms. Amongst infectious diseases, it is the number one global killer: Tuberculosis.

Before COVID-19, over 4,000 people were dying from TB every day.

According to new estimates published in the European Respiratory Journal, and WHO projections, that number could rise significantly if there is substantial health care disruption and social distancing measures aren’t adequate.

Models predict between 100,000 and 200,000 additional TB deaths over the next five years in India, China and South Africa alone, and WHO project double that number globally if detection and treatment falls, even for a few months, undoing the good work that has been painstakingly achieved around the world to stem the growth of this increasingly drug-resistant disease.

TB has always been an opportunist, taking advantage of compromised immune systems and natural disasters since the Ancient Egyptians.

As one of my characters, Mary, says in The Waiting Rooms:

‘Let’s face it, anything that can flourish for three million years must be pretty adept at survival.’

Current thinking is that having pulmonary TB does not make you more likely to contract COVID-19, but if you do fall ill, the severity of the infection is likely to be worse because of existing damage in the lungs. And if your treatment for TB is disrupted, especially if it’s a

drug-resistant strain, then the predicted outcomes are not good.

“TB is a disease of poverty, and economic distress; vulnerability, marginalization, stigma and discrimination are often faced by people affected by TB.

TB is curable and preventable. About 85% of people who develop TB disease can be successfully treated with a 6-month drug regimen.”

There were 465,000 new cases of drug-resistant TB in 2019, of which 78% were resistant to the 2 most powerful first-line anti-TB drugs.

Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) caused an estimated 206,000 deaths globally in 2017: a figure that could increase to 2.5 million deaths per year by 2050 under the most alarming scenario, if no action is taken. India, China and Russia account for half of all MDR-TB cases.

If we have learned anything from the COVID-19 pandemic, it is that we need to take notice and take action when the world’s scientific community and health institutions tell us there is a problem. In The Waiting Rooms, there are many calls for action in the decades leading up to the antibiotic crisis. Calls that, despite the very real evidence of impending disaster, fall on deaf ears.

As my character, Mary, comments: ‘It’s like watching a plane crash, in slow motion.’

I appreciate this isn’t very cheery. But then, if you have read The Waiting Rooms, you wouldn’t expect it to be. There is a global TB pandemic happening, right now. But in the real world, at least for the time being, the majority of patients can still be treated with drugs that work.

By illustrating the very real horrors of a world where antibiotics no longer work, the hard choices inflicted on society when infections run rampant, and demonstrating just how easily that could happen, I am hoping that, in its own small way, The Waiting Rooms will contribute to awareness about antimicrobial resistance. Maybe even nudge a few of those actions further along.

Because this story needs to remain fictional.

We’ve got more than enough dystopia in our lives to cope with.